Search WCSU

WCSU Essentials

Automatic translation disclaimer

Translation of this page is provided by the third-party Google Translate service. In case of dispute, the original language content should prevail.

La traducción de esta página la proporciona el servicio Google Translate de terceros. En caso de disputa, prevalecerá el contenido del idioma original.

La traduction de cette page est fournie par le service tiers Google Translate. En cas de litige, le contenu de la langue originale prévaudra.

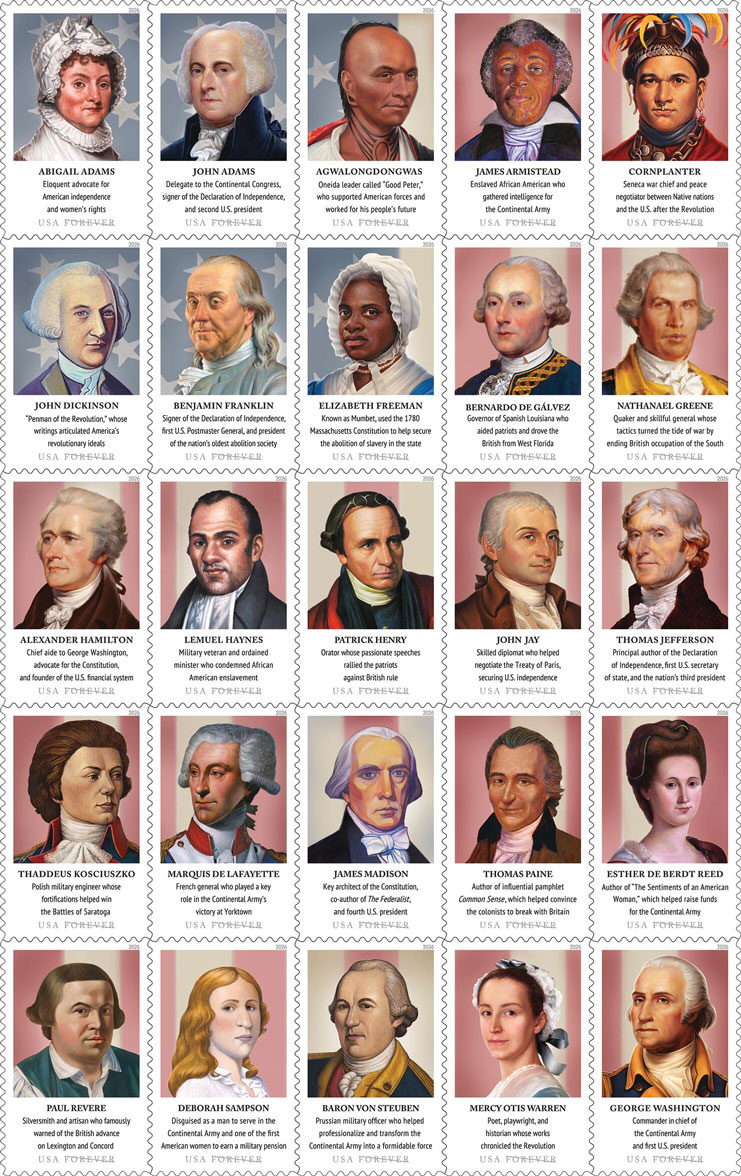

Gutzman Stamps Out Errors for Semiquincentennial

History Professor Dr. Kevin Gutzman has written hefty books about Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. He immerses himself in museums and libraries while researching catalogs of details about the men and women behind the Revolutionary War.

Yet his latest assignment was to ensure the accuracy of just three short lines — fewer than a dozen words each — about Jefferson, Madison, George Washington and 22 others who played roles in American independence.

Gutzman’s imparting of knowledge was confined by his most recent mode of communication — not a book or lecture, but one postage stamp for each person deemed worthy of recognition by the U.S. Postal Service for the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Indepenence.

Gutzman described his role as “expert copy editor” for the text on the stamps, and in an accompanying pamphlet. “I was supposed to tell them whether the things they said about the people on the stamps were accurate,” he said. “Sometimes I suggested that what they had was not going to work. Most of it was fine but some things needed refinement.”

The result, he said, while not exactly how he would relay it in a class he might teach, was satisfying.

“I think that having this information on stamps gives people an opportunity to learn about this part of history, for those who normally don’t think about it. It will have a good didactic effect on people who see it.”

Gutzman speaks concisely and with care. It’s easy to imagine his students consider him stern as he lectures and challenges them. “Who is Connecticut’s most famous Revolutionary,” he asks, pausing for an answer. “Benedict Arnold!”

Visiting his grandparents in Idaho during the nation’s 1976 bicentennial (he was 13), Gutzman’s interest in history was piqued as he watched the Parade of Ships in the New York Harbor along with festivities in Philadelphia and Charleston, South Carolina. It also helped that his parents, whose family went back generations in Idaho, took the boys on cross-country vacations.

Gutzman earned a bachelor’s degree in history from the University of Texas and law degree from the University of Texas School of Law. He practiced briefly as an attorney, but found it uninteresting. His next stop was at the University of Virginia, founded by Thomas Jefferson, where he earned his master’s in history, followed by a Ph.D. that enabled him to teach and “make a difference.”

While serving at WestConn for 24 years, he has published extensively, consulted for television and radio, and presented at prestigious conferences. With the approach of the semiquincentennial, as it is called, Gutzman has received a new wave of requests, in addition to that from the Postal Service.

In just the past several months, he has been invited to a research fellowship at the campus of the American Institute for Economic Research in Massachusetts, hired as editor-in-chief of a commemorative issue on the semiquincentennial, given the annual Constitution Day address at Clemson University, and written an essay on the state and future of James Madison biography at the Madison Papers project housed at the University of Virginia.

He recently completed an assignment from The Heritage Foundation, which is publishing essays from each state on Revolutionary War-era sites worthy of notice. Gutzman wrote about the Windsor homestead of Oliver Ellsworth, who was a framer at the Philadelphia Convention, U.S. senator, and third chief justice of the United States, and the Litchfield Law School, where Aaron Burr and John C. Calhoun, both vice presidents, and several state Supreme Court justices, U.S. senators, and cabinet officers went to law school.

Even with that background, Gutzman said he didn’t expect the call from the USPS.

Just out of the blue they asked me to do this,” he said. “I was flattered.”

When he received the materials to edit, he was surprised to find he was unfamiliar with some of the selections, including Bernardo de Gálvez. “He was a Spanish admiral I had never heard of,” which Gutzman admitted he found irritating. “They left out de Grasse, the French admiral who was actually on the spot at Yorktown and made it impossible for the English to escape.” It wasn’t Gutzman’s list, though, so he kept his frustration to himself.

He also acknowledged that he made one error, although it did not make it into the stamp collection or materials that will accompany them.

Thomas Paine, the pamphleteer who helped whip up rebel fury, was born in England and changed the spelling of his name from Tom Pain after arriving in the colonies. Gutzman got the Pain-to-Paine sequence backward and was gently corrected by his USPS editor.

Gutzman offered other edits in notations like this:

Abigail Adams encouraged John, not “leaders,” “notably advising him,” not “them,” to “remember the ladies.”

In paragraph four, it should be “his midnight ride.”

In paragraph 10, after “concluded hostilities” I’d say, “secured international recognition of American independence, and — thanks to Jay — recognized the Mississippi River, rather than the Appalachian Mountains, as America’s western boundary.” (This was arguably the greatest diplomatic feat in American history. (I know: my version is kind of wordy, but without it, we can’t see why we chose Jay alone of the American negotiating team to mention.)

The USPS also asked Gutzman about his opinion about the placement of the 25 figures within the stamp pane.

“George Washington was the most important person in the revolution, Gutzman said. “You should put him first.”

As published, the listing is alphabetical, with Washington last and, in Gutzman’s opinion, “in a place people won’t notice him.”

When the stamps are officially released early in 2026, Gutzman expects an invitation to the celebration in Washington, D.C. He said he’s not sure he will attend, but he has thought about the significance of a project that historians and Postal Service artists will refer to in advance of the nation’s tricentennial, and perhaps even 250 years from now, assuming postage stamps are still being used in some form.

Gutzman takes the long view.

“When I was an undergraduate, I read Sallust, the Greek historian, who wrote “The ‘Conspiracy of Catiline.’ In the introduction to the book, Sallust is quoted as saying that a good book is a better legacy than a fortune. As an attorney I was bored. I hope this effort will have the effect of getting some people interested in the subject.”